by Stefan Linz & Jxli Bixie Eutsler / Illustrations by Kayla Fincken

Welcome to this reader! We want to introduce you to some basic ideas and discussions from the realm of academic peace studies: What is peace, what is its opposite, what is the difference between violence and aggression, and when (if ever) might violence be justified?

More important than answering questions, however, is posing them: The different sections of this reader are not in any way meant to provide you with definite or even complete answers – they are meant as a starting point for your reflections on peace. Our hope is that by providing more accessible theory, people can learn from what academics have to say about the fields they are working in, and take something from that to improve their own work. We hope that will be true for you, too!

We very much tried to keep our texts be as accessible as possible, but since this work is based on a university course (Anthropological Analyses of War and Peace), and most texts we write are essays and other student papers, it might be a bit hard to digest at times. If you find something particularly hard to follow, nonsensical or just worth your comment, don’t hesitate to drop us a line!

Also: If you would want to know more about a specific point made, you could refer to the Literature section at the end of this reader.

Peace Studies and Related Fields

Peace studies are related to many other areas of knowledge; we will show intersections with anthropology, psychology, political science, gender and media studies.

For instance, Sponsel writes about the ways Peace Studies and Anthropology complement each other in the article The Mutual Relevance of Anthropology and Peace Studies. The table below illustrates the major overlaps highlighted in this article. The middle column shows elements the fields already share. The outer columns are elements specific to one field or the other. Elements with a plus are positive features the field could share with the other, while elements with a minus are negative features that the other field could correct or make up for.

| Anthropology | Both | Peace Studies |

| breadth and diversity

cross-cultural and cross-species comparisons view of widely varying time periods importance of empathy theories of human nature self-reflection often, a heavy focus on violence (on negative peace or the absence of it) |

interdisciplinary approaches

holistic and historically based emphasis on global thinking |

possible catalyst for rethinking older ideas and theories

background for understanding militarization and political (IR) aspects of peace counter focus on war, encourage focus on positive peace development current goal (encouraging peace in our modern societies) contributed to by many specialized fields (may narrow its view of the subject) |

But what other fields are relevant to peace studies? Many interdisciplinary fields share similar methods or subject matter that may already be quite compatible with peace studies as well. Below a few are illustrated.

| Pedagogy and Psychology | Both | Peace Studies |

| “Teaching for Peace” (at societal and interpersonal levels)

imparting ideas of peace studies to public consciousness (to influence society from that level) |

framing subjects in a way that encourages useful discussion and further development | striving towards positive peace → increase equity of education → reduction of structural violence

specialized theory and debates remove subject from people at large |

| Political Science | Both | Peace Studies |

| view of warfare, diplomacy, and other state relations on a policy level

policy background can provide information on how to achieve peace in modern states modern examples in today’s societies warfare and negative peace emphasised generally state-centered |

focus on interactions between multiple actors

value both warfare and diplomacy heavy emphasis on conflict resolution |

push towards positive view of peace can encourage social justice

introduction and emphasis of peaceful forms of conflict resolution likely to highlight alternatives to the state much theory views the state as inherently violent, possibly making this partnership a tense one |

| Gender Studies | Both | Peace Studies |

| shift of focus towards members of society who are generally left out of war-centered studies

thoroughly articulated view of patriarchal structural violence can expand discussion of structural violence in general queer studies provides models for nonbinary descriptions (which can assist in expanding the discussion of peace from simply violent/nonviolent or other binary assertions) provides a view of the role gender plays in violence view of social ills often limited to the effects of patriarchy; not always the most intersectional |

agenda-oriented: working towards social justice; studies go hand in hand with activism

focus on relations between different groups ideally both fields globally focussed and taking various cultures into account, but often limited by researcher’s own perspectives |

view of positive peace and structural violence widens view of oppression beyond just the patriarchy

weaves gender specific issues into a wider view of societies |

| Media Studies | Both | Peace Studies |

| reveals nuances of how societies view peace and warfare, particularly through different time periods

insight into military as viewed by civilians insight into how people are convinced of the necessity of war (propaganda) can reveal how media can be used to sway public opinion (such as by encouraging peace) often highlights war over peace says more about society that created the media than about how it relates to others |

relate to ways societies see themselves and their place in the world

researchers must be aware of own cultural biases and of who tells which stories |

focus on relations between represented groups

can emphasise importance of views of the world that encourage peace (“Why is it important that we, and in turn our media, encourage peace?”) does not always reflect complexities of views of warfare in a society, especially over time |

Nature versus Nurture

“Nature versus Nurture” (or “Nature versus Culture”) is one of those popular scientific buzzwords that gets brought up time and again. But what does it refer to?

However, it is important to recognize that this is not at its core a scientific debate, but rather a moral, philosophical, and political one – originally rising from the work of thinkers such as Hobbes or Rousseau. While the former believed in the violent nature of humans, the latter argued against this view. For a long time the accepted view was that humans are naturally violent and immoral and must be disciplined or nurtured into good behavior, as Hobbes suggested. A major problem with this view was that it has often been used in racist and colonial ways to argue that people outside of western societies have not been nurtured or “civilized” in the way that Europeans have.

Ultimately, when it comes to this debate, it may be best for us all to take a step back, shrug, and ask:

Aggression and violence can be encouraged or discouraged by a person’s environment, so the more interesting question might be how a given culture deals with these human tendencies.

Antiquity of Warfare

Were our ancestors bloodthirsty killers or mostly peaceful? Is it even useful to think in such polarised terms?

Well, probably not. This view of early humanity is popularly accepted, especially from a western standpoint, because it backs up the philosophical assumption that humanity is by nature cruel and violent, as illustrated by Graham Kemp in The Concept of Peaceful Societies. However, growing evidence shows that this was likely not the case. There is a good chance that violence, especially on more complex scales, is not nearly as ancient as some would like to believe. There are many reasons for this, including the fact that cooperation, not competition, would have facilitated the survival of early humans. Additionally, space and resources were plentiful, meaning there would be not much reason for group conflict. However, the view of early humans as warring creatures persists.

The Legend of the “Killer Ape”

The “Killer Ape” legend states that humankind has always been battle-happy. Primates are violent, our ancestors were violent, we are violent; therefore violence is simply a part of who we are, right?

Clearly this argument rests heavily on both the “nature” half of the “Nature versus Nurture” debate, and the argument that violence has always existed in human societies and grown more complex with them – violence becoming warfare. The idea of the “Killer Ape” also upholds the common western viewpoint that humankind is inherently destructive, violent, or otherwise “sinful”. Without these former ideas being widely accepted as self-evident truths, this legend of the “Killer Ape” would likely not have the hold on popular imagination that it currently does: The “Killer Ape” plays out both in popular consciousness and in anthropological literature. We see it time and again from descriptions of the earliest Hominids, to analyses of Chimpanzee behavior, to justifications of (predominantly male) violence.

Though this legend still thrives in the popular imagination, it has faced some scrutiny from an academic standpoint. Pinker’s List, an article by Brian Ferguson, attempted to show the exaggerations of human violence in prehistoric times and disprove the statement that war has been common throughout human history.

Violence versus Aggression

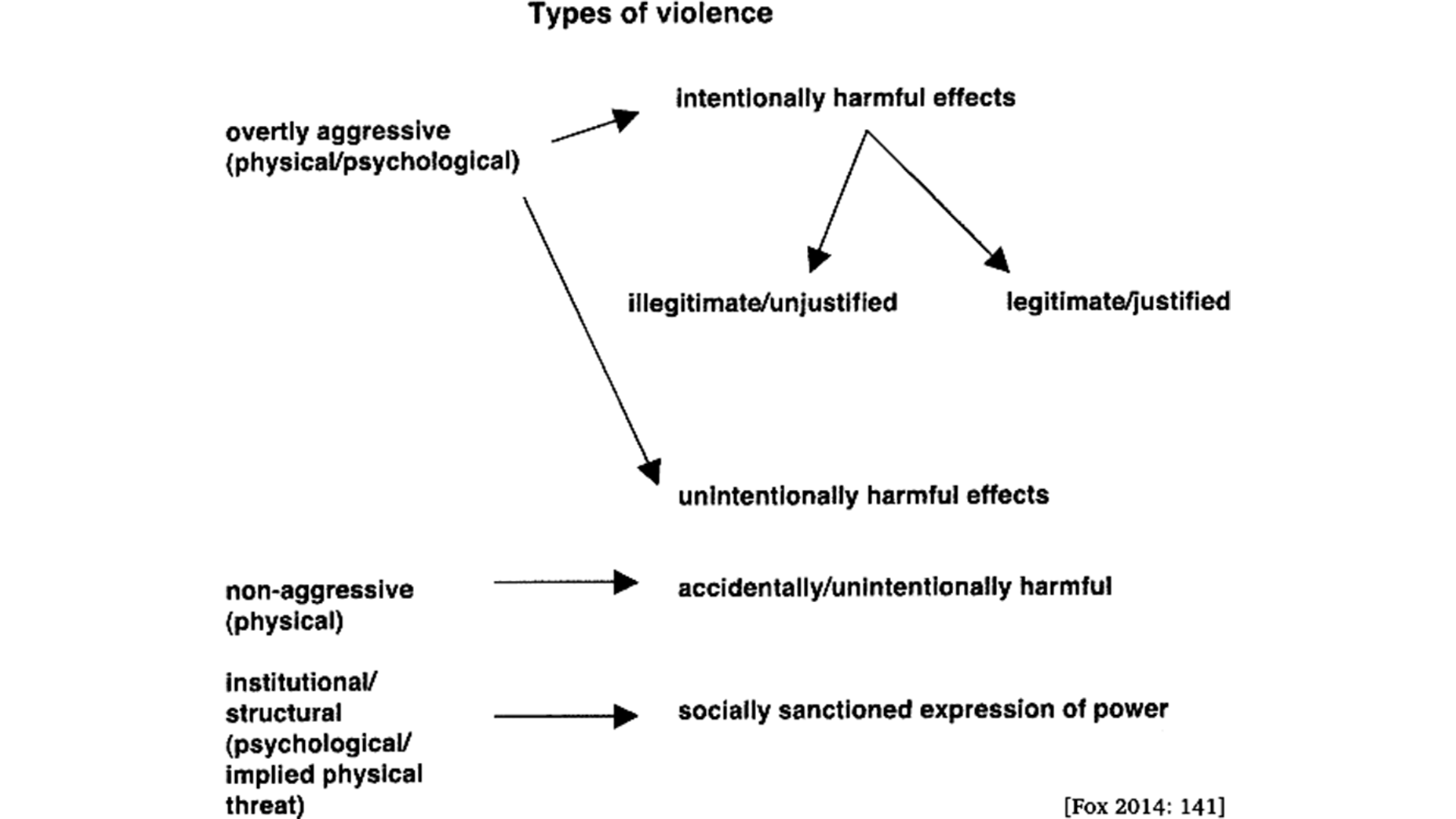

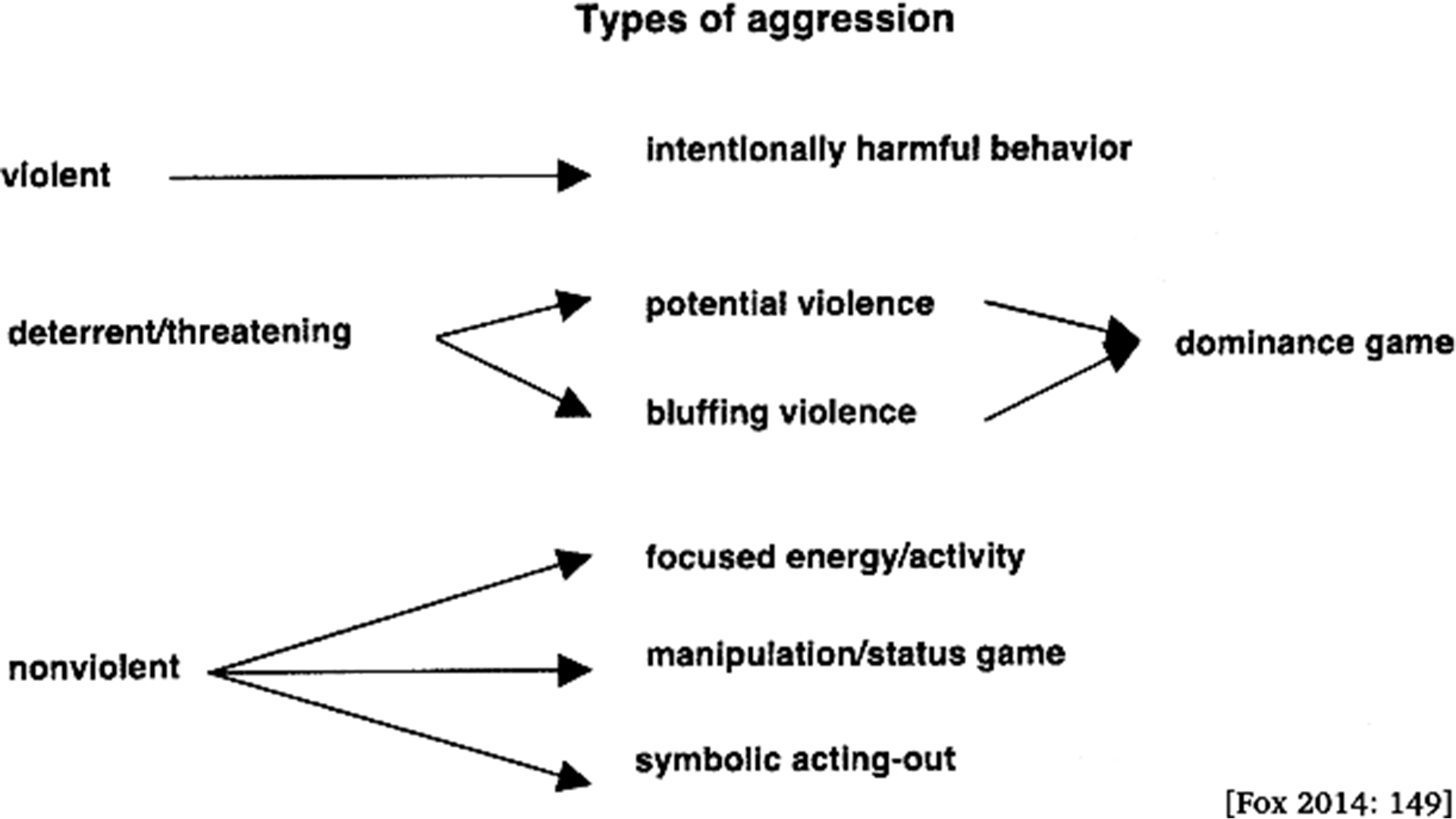

Much like with peace itself, it has been very difficult to find a common definition of violence and aggression; we will discuss one anthropologist’s attempt at it.

|

|

In his view, “violence” would mean “force, coercion, or psychological manipulation of any kind, used in a harmful or destructive way against some being that has an interest in not being harmed or destroyed; or that is used reflexively by one who has abandoned this interest; or that is used against an object or entity some being has an interest in not seeing harmed or destroyed”. Further, he states that “[w]hile most expressions of violence may reasonably be called aggression, aggression is not necessarily or always violent”. We do not agree with this interpretation. In fact, we feel that the opposite is more correct: While most expressions of violence may be called aggression, violence is not necessarily or always aggressive. Aggression, even in the examples mentioned above by Fox, requires some amount of emotional investment. There is some motivation for the aggressive behavior, even if it is simply to cause others unhappiness. Violence, on the other hand, does not need this reason or emotion behind it. We argue that violence could be defined as any act, whether committed by one person, many, or a system, that reduces the quality of life of another person or group, while aggression is any action that purposely evokes a negative reaction from or causes harm to another person or group. This definition gives us a much wider view of violence, and it allows us to look at structural violence despite it not being inherently aggressive.

Structural violence, as coined by Galtung, is violence that is indirect and often unintended, often resulting from unjust structures. Many individuals who uphold violent structures and institutions may feel that they are simply following rules or doing their job. This leads them to harm others without being aggressive towards them.

Let us consider the SAT, a test mandatory for admittance into many U.S. colleges: Imagine a student wishes to take the SAT so that they may submit their results to a university in hope of being accepted. This particular year, the test costs $65, an amount this student’s family simply cannot pay. If this student shows up anyway and is denied a test, the individuals facilitating the test would likely feel that they have acted right, enforcing the policy that everyone must pay to take the test. However, they have been agents of structural violence by denying the student (and by extension lower-income families) a method of accessing higher education.

Positive and Negative Peace

Like any other topic, in order to be able to talk about peace, we have to agree on what it is. There is no one answer to this, but there are some generally agreed upon terms.

Two simple, yet very different understandings of peace are Positive and Negative Peace. Galtung speaks about these in his article “Peace, Negative and Positive”: Quite the fitting name. Negative peace is what many western cultures hold up as an ideal state: There is no outside conflict or war and no immediate threat of conflict, so the society is at peace. Positive peace takes a much wider view: There is no external conflict or threat of external conflict, but there is also as little other suffering as possible within the society. This means that ideally there would be no structural violence (inequality, poverty, oppression), as well as no direct violence. This form of peace strives for economic and social justice and harmony, as Gregor points out in his Natural History of Peace.

Galtung also stresses that peace is a property of relationships between people or societies: No society can create peace or war on its own.

Mapping Peace Concepts

Because one can be easily confused sometimes by the sheer amount and different usage of all these terms, we try to bring some of them together in a systematic way.

One involves dividing peace into Inner peace, Outer Peace, and Interpersonal or Intersubjective Peace. A second model divides peace into internal and external, both on a state and personal basis.

With a bit of creativity, it is possible to map these concepts over each other to compare them and gain an even more complex view of peace:

Civil Society

Interactions between individuals are very important for peace efforts; the term “Civil Society” comes up in that context a lot. What does it mean though?

Catherine Barnes, in her 2009 article Civil Society and Peacebuilding: Mapping Functions in Working for Peace, talks about how “(…) the complexity, scale and diversity of violent conflict means that no single entity, on its own, can hope to adequately address the challenge of ensuring sustainable peace.” So what she and many other academics, politicians and other public voices suggest is that we focus on something that has come to be called “Civil Society”: The amorphous entirety of all groups that stake their claim in a society. This term is also inextricably linked with the Liberal Peace concept (explained in the next chapter).

Civil Society, Barnes says, can serve eight main functions to “build” and maintain peace:

| 1. “Waging conflict constructively”

(Debate, do not hurt each other!) 2. “Shifting conflict attitudes” (Do I really have to reach my goals in a struggle against you and others, or could we cooperate?) 3. “Defining the Peace Agenda” (What has to be done to end violence & conflict?) |

|

| 4. “Mobilising constituencies for Peace”

(We all want peace and we say it out loud!) 5. “Reducing violence and promoting stability” (So we can feel safe in our community.) |

|

| 6. “Peacemaking / Conflict Resolution”

(People get together and find ways to settle conflicts.) 7. “Community-level Peacemaking” (Start small: Conflicts settled on the level of neighborhoods, not states.) |

|

| 8. “Changing root causes and building cultures of Peace”

(Find ways to erase whatever makes people feel they should or need to act violently against others.) |

|

A lot of this is probably obvious, but there is another interesting point in Barnes’ article: While coercion, be it by local or international peacekeepers, can encourage or even force an actor contributing to conflict to behave more peacefully, this will only be a temporary fix and will not solve the root conflict that triggers the violent behavior. As Barnes puts it: “Making peace [means] helping to reach agreement.” So in order to have any chance of reaching something we might call “sustainable peace”, all parties involved in a given conflict would have to reach some kind of mutual understanding and agree on the most basic terms and conditions of living, if not with, then next to each other:

“Sustainable peace processes need to be about more than finding ways to end the fighting; attention must also be directed to supporting societies on the path towards a more equitable and peaceful future.”

Liberal Peace

Civil Society is often linked to the concept of “Liberal Peace”, a theory that claims democracies are less likely to be in conflict with each other. We have some critique.

An interesting aspect of this approach is that it focuses on describing (liberal democratic) states’ motives for enacting less violence (at least between each other), instead of trying to explain why they are at war with each other. We might say this is indeed a “theory of peace”.

But what does “Civil Society” have to do with this? Well, liberal democracies, or more specifically their ruling elites (governments, military and industrial leadership, intellectuals) tend to look at other societies dealing with violent conflict and think: “If only they were more like us, they would be able to live together more peacefully.” Some authors, like anthropologist Paul Heelas, have described how problematic this approach can be and argue for more attention to specific conditions and environments.

One author who focuses on this problem a lot in his writings is Oliver P. Richmond. To illustrate his critique of what is often called “liberal peacebuilding”, we will now take a short look at his 2018 article Rescuing Peacebuilding? Anthropology and Peace Formation.

Richmond argues that due to its “neoliberal epistemological frameworks” (fancy language for having a neoliberal mindset), liberal peacebuilding’s perspective puts local actors into a “blind spot” – we might even say liberal peacebuilding is afraid of local perspectives:

|

“When mainstream (…) International Relations (IR) scholars and policymakers view the world they are endeavouring to govern, pacify, make compliant or liberate, they perceive problems to be solved with sophisticated material, (…) including the need to refine that world via state or global governmentality (…).” |

So if we unpack this quote, we see two main points: Firstly, as already hinted at above, liberal peacebuilding initiatives stem from a concept that tries to copy existing state systems and erect liberal democracies, while refining problems in terms of (from their perspective!) familiar modes of governmentality, often without regard to local circumstances. Secondly, the erection of liberal democracies requires the transformation of people – who used to consider themselves either subjects or did not consider themselves anything in relation to the state – into citizens (the establishment of a “Civil Society”, if you want), as Richmond further describes:

|

“This project [liberal peacebuilding] is one of pacification and governance (local, state or global) whereby its subjects’ needs and identities are not engaged with directly. According to the principles of the liberal, they are to be ‘transformed’ into rights-observing and rights-bearing subjects in a neoliberal world of self-help, so that local, state and systemic conflict may be avoided.” |

So where does that leave us? How could we potentially improve our approaches on peacemaking?

While one obvious answer would be to stop ignoring local agency and perspectives, the question remains of how to go about that. Here, anthropology might help: In order to “save” peacebuilding from its crises, Richmond suggests interdisciplinary approaches (involving two or more academic fields, or disciplines). Also important would be to interact on a “level playing field”, for “peace formation”, as Richmond calls his vision of a better approach to ending conflict, would mean taking local perspectives seriously:

|

“Mainstream IR and mainstream peace and conflict studies tend to see culture as (…) too complicated to be included in [peacebuilding]. (…) More anthropological and ethnographic views see culture, society, identity (…) as a significant and often political site of human agency, essential for the mediation of difference upon which institutions necessarily rest.” |

This would also mean giving both international (or intervening), as well as local (or intervened upon) groups a stake in the building of sustainable societal peace:

|

“Peace formation means bottom-up rather than top-down empowerment (…) for all the latter’s risks.” |

Conflict Resolution Strategies

Here we take a closer look at what ways there are for people to reach common ground and work through conflict.

This chapter deals with “Conflict Resolution Strategies”, as described by anthropologist Douglas P. Fry in chapter three of his book The Human Potential for Peace: An Anthropological Challenge to Assumptions about War and Violence, published in 2006. The next chapter will deal with the concept of “Nonviolent Communication”, before we go back to a more meta (“above the things”) perspective by looking at how violence might sometimes (not) serve peace, how different worldviews warrant different approaches to peace, and how peace and conflict are portrayed in media. But first, for Fry and different strategies of conflict resolution.

According to him, there are five different types of conflict-management, affected by social organization and cultural systems in a given society: He differentiates between unilateral or bilateral approaches (self-redress, avoidance, toleration, negotiation) on the one hand and trilateral approaches (third-party assisted settlements) on the other.

| Unilateral and Bilateral Approaches | |

| 1. Self-Redress (Self-Help, Coercion)

(potentially involving physical aggression; unilateral action in an attempt to prevail in dispute or punish disputant/s) |

|

| 2. Avoidance

(short to long term) |

|

| 3. Toleration

4. Negotiation (potentially involving giving & accepting compensation) |

|

| Trilateral approach | |

5. (Third-party assisted) Settlement

|

|

Another interesting aspect in Fry’s work is the distinction between “antiviolent” and “nonviolent” behavior: Even though he himself does not expand on it much, this distinction might be useful for naming the difference between a value system that punishes any expression of violence (“antiviolent”) and a value system that accepts expressions of violence under special circumstances, like the protection of life from overt or unjustified external violence (“nonviolent”). Whether a value system that legitimizes (the threat of) force for the enforcement of peace (“Repressive Peacemaking”) could still be called nonviolent is up for debate.

In this context, the different terms used to describe how peace comes to be are also worth thinking about: What is the difference between “Peacemaking” and “Peacebuilding”?

Nonviolent Communication

Effective communication skills help promote peace. Whether in personal relationships or on a community level, the ability to express needs and desires is vital.

“Nonviolent Communication” is a particular method of communication and approach to nonviolent living developed by Marshall Rosenberg in the 1960s. Here we will provide a brief overview. At its heart, nonviolent communication consists of four aspects: Observations, feelings, needs, and requests.

1. Observations: What do you notice in the current situation?

2. Feelings: How do different aspects of the situation make you feel? Why?

3. Needs: What do you need? What needs are not being met?

4. Requests: What can the other person do to help meet your needs?

In order to be effective, participants must approach this method with empathy and honesty. These four aspects can then be incorporated into a dialogue:

1. When I see __________,

2. I feel __________,

3. because I need __________.

4. Would you be willing to __________?

Another useful method of communication is the I-message, a term coined by Thomas Gordon. This is the method of speaking from your own perspective using statements that begin with “I” instead of making general statements. This allows the speaker to be assertive about their needs and feelings without putting the listener on the defensive, as Michelle Adams points out. For example one could say “I could not find my house keys, because they were not where they belong.” instead of “You did not put my house keys back after you borrowed them.”

There are many other methods that can be similarly helpful. The important thing really is to find an effective way to communicate your feelings and needs without further escalating the conflict.

The (possible) Role of Violence in the Quest for Peace

Can peace be reached by violent means? And if so, under what circumstances and conditions could violence be justifiable?

Instead of answering the question “What can the role of violence be in the quest for peace?”, we want to discuss two examples, to illustrate some circumstances in which the use of violent means was seen as legitimate.

One requirement for violence to be seen as legitimate is the “use of limited and proportionate violence in order to protect the own and/or vulnerable groups and/or to prevent greater evil”. In the context of protest movements and rebellions, questions concerning the role of violence are often hotly debated: Some argue that using militant tactics contradicts the overall strategy and runs counter to the struggle’s (peaceful) agenda, while others say that more militant approaches are justified and useful to stop other (more severe) direct or indirect violence.

A particularly illustrative example of this debate is the “Hambacher Forst” occupation, located near Cologne, initially an anti-coal mining squat in resistance to the expansion of open lignite mining. Activists who participated in the movement, which formed around the initial occupation since the first squat was erected in 2012, repeatedly discussed the issue of militancy and how it enhances or subverts their cause(s). These debates focused on the argument of “(self-)defense” and prevention of “greater evil”:

“Wouldn’t it even be irresponsible not to act violently, if worse could be averted? (…) it can also be hard not to put up resistance when police beats you up and you are faced with the destruction unleashed by RW€ [sic!] every single day.”

The issue of mainstream acceptance and militant tactics was hotly debated in late 2018, when the resistance against lignite mining and the company RWE came to the attention of a broader public, in part due to excellent social media campaigning under the hashtag #hambibleibt. Many more (left-)radical and anarchist activists pointed out that the struggle they had already been invested in was now taken over by environmentalist NGOs, with the result being a narrow focus on (anti-violent) anti-lignite protest and a tabooization of militant tactics that had been widely used for years.

More prominent, at least in national and international media, and more extreme in regards to both quality and dimensions of the violence exerted, are military interventions: Intervening into (already or potentially armed) conflicts always bears the risk of provoking an escalation, cementing existing resentment and installing new divisions, as the recent history of so-called “humanitarian interventions” shows – from Libya to Afghanistan, from Iraq to Somalia. In the context of UN-“Blue Helmet” mandates, however, there is generally less debate about the pros and cons of using violent means; commentators (and blue helmets themselves) rather argue that the nature of these missions necessitates limited and proportionate militant violence in order to protect vulnerable groups at risk of being victimized. Concerning this, Roméo Dallaire, retired Lieutenant General and commander of the UNAMIR force that failed to prevent the Rwandan Genocide in 1994, states:

“Could we have prevented the resumption of the civil war and the genocide? The short answer is yes. (…) [C]ould we have stopped the killings? Yes, absolutely. Would we have risked more UN casualties? Yes, but surely soldiers and peacekeeping nations should be prepared to pay the price of safeguarding human life and human rights.”

The big question then is, of course, how to deal with the perpetrators. As Catherine Barnes, says: Counter-violence or the use of overwhelming force to dragoon conflicting parties into a (negative) peace can only ever be a temporary fix; coercion can never be a basis for sustainable peace, be it positive or negative.

Worldviews and Peace

Peace Studies have an unfortunate tendency to present western liberal democracies as the best model for maintaining peace – we want to showcase alternatives.

Let us take, for example, the Semai of the Xingu River in Brazil. This small, tropical forest society relies mostly on fishing, hunting, and agriculture. Social structures are predominantly egalitarian, and organized by kin groups (as described by Gregor and Robarchek) – a far cry from the more complex structures imagined by many peacemakers. And yet, this society lives in peace. How? The answer comes down to mostly worldview and values: The kin group is viewed as the only source of protection against the harsh outside world; harmony within the group is highly valued and conflict is avoided at all costs. Complex systems of taboos and conflict resolution exist to help maintain group harmony.

Effective peacemaking must be as dependent on cultural context as maintaining peace is, so that the process truly resonates with the groups involved. This was showcased in the 1993 ritual to establish peace between twelve groups in the Ethiopian Rift Valley: Representatives of the Abore (Hor), Borana, Konso, Tsamai, Hamar, and Dassanech initiated the ceremony and were joined by members of six other groups. Together with NGOs, administrators and anthropologists, they met in a place of mutual importance, a patch of land that had been laid barren by prior warfare. Here, and in the nearby shade they erected together, they discussed their differences in order to establish a peaceful path forward. Together they enacted a peace ritual that drew on shared symbolism and practices, which allowed them to reach a conclusion that was significant for all groups present. Though the entire process was filmed and written about by anthropologist Alula Pankhurst (whose footage in part constitutes the 2004 documentary “Bury the Spear!”) and attended by government officials, it was facilitated only by the groups themselves, enhancing their commitment to the established peace.

By establishing peace in a culturally specific way, these groups forged a lasting bond that was far stronger than any peace enforced from the outside would have likely been. As each group saw itself represented in the proceedings, they were involved and invested in each step of the process. For peace to truly take hold it must mingle with everyday life and culture: There is no one correct way to peace, but rather many different paths.

Peace and War in Media

War is a timeless theme in media – peace, on the other hand, seems to be unattainable, even in fiction. How come?

Media does more than just entertain. It reflects our society and ideals, and it can shape the way we see the world. Knowing this, how should we approach war and peace in media?

Some pieces of media obviously glorify warfare. They make it look fun, honorable, and exciting. But even when this is not the case, portrayals of violence can be a tricky moral question when we are on the search for peace. Where is the line between entertainment and societal influence?

There is no easy answer to that question. It has been encountered time and again, from christian fundamentalists arguing against “violent” music to feminist theorists insisting that all pornography encourages misogyny (see Susan Fraiman’s text for more on this view).

Here, we need to once again take a step back and see that this is a nuanced problem that has to be decided upon individually on a case by case basis. As both creators and consumers we have the responsibility to constantly evaluate the impact our media has on ourselves and others, but it must be just that: A constant evaluation. There is no easy answer and the importance of each piece of media shifts with time and political context.

Literature

Our list of our readings – we reference them at times, and the list provides some very interesting links to (mostly academic) writings on peace, ordered by chapter.

Sponsel, Leslie E (1994): “The Mutual Relevance of Anthropology and Peace Studies.” In Leslie E. Sponsel & Thomas Gregor (Ed.): “The Anthropology. of Peace and Nonviolence.”, 1-36. Boulder and London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Nature versus Nurture

Kemp, Graham (2004): “The Concept of Peaceful Societies.” In Graham Kemp and Douglas P. Fry (Ed.): “Keeping the Peace: Conflict Resolution and Peaceful Societies Around the World.”, 1-10. New York and London: Routledge.

Antiquity of Violence

Ferguson, Brian R (2013): “Pinker’s List: Exaggerating War Mortality”: In Douglas P. Fry (Ed.): “War, Peace, and Human Nature.”, 112-131. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kemp, Graham (2004): “The Concept of Peaceful Societies.” In Graham Kemp and Douglas P. Fry (Ed.): “Keeping the Peace: Conflict Resolution and Peaceful Societies Around the World.”, 1-10. New York and London: Routledge.

Violence versus Aggression

CollegeBoard (2018): “Fees.” SAT Suite of Assessments, 15/11/2018. [09/02/2019]

Fox, Michael Allen (2014): “Understanding Peace: A Comprehensive Introduction.” New York and London: Routledge.

Galtung, Johan (2010): “Peace, Negative and Positive,” in Nigel Young (Ed.): “The Oxford International Encyclopedia of Peace. Vol. 3.”, 352-356. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Positive and Negative Peace

Galtung, Johan (2010): “Peace, Negative and Positive,” in Nigel Young (Ed.): “The Oxford International Encyclopedia of Peace. Vol. 3.”, 352-356. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gregor, Thomas (1996): “Introduction,” in Thomas Gregor (Ed.): “A Natural History of Peace.”, ix-xxiii. Nashville and London: Vanderbilt University Press.

Mapping Peace Concepts

Webel, Charles (2007): “Introduction: Toward a Philosophy and Metapsychology of Peace.” In Charles Webel and Johan Galtung (Ed.): “Handbook of Peace and Conflict Studies.”, 3-13. London and New York: Routledge.

Civil Society

Barnes, Catherine (2009): “Civil Society and Peacebuilding: Mapping Functions in Working for Peace.” The International Spectator: Italian Journal of International Affairs 44 (1): 131-147.

Liberal Peace

Abulof, Uriel & Ogen Goldman (2015): “The Domestic Democratic Peace in the Middle East.” International Journal of Conflict and Violence 9 (5): 1-17.

Doyle, Michael (1983): “Kant, Liberal Legacies, and Foreign Affairs.” Philosophy and Public Affairs 12 (1): 205-208.

Heelas, Paul (1989): “Identifying Peaceful Societies.” In Signe Howell & Roy Willis (Ed.): “Societies at Peace: Anthropological perspectives.”, 225-243. London and New York: Routledge.

Richmond, Oliver P. (2018): “Rescuing Peacebuilding? Anthropology and Peace Formation.” Global Society 32 (2): 221-239.

Conflict Resolution Strategies

Fry, Douglas P. (2006): “The Human Potential for Peace: An Anthropological Challenge to Assumptions about War and Violence.” Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nonviolent Communication

Adams, Michelle (2012): “What are the Essential Components of an I-Message?” Gordon Training International, 31/05/2012. [09/02/2019]

Rosenberg, Marshall (2003): “Nonviolent Communication: A Language of Life.” Encinitas: Puddle Dancer Press.

The (possible) Role of Violence in the Quest for Peace

Barnes, Catherine (2009): “Civil Society and Peacebuilding: Mapping Functions in Working for Peace.” The International Spectator 44 (1): 131-147.

Dallaire, Roméo (2014): “Shake Hands with the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda.” New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers.

Hambacher Forst (2012): “RWE und Polizei versuchen, die eigene Gewalt mit unhaltbaren Vorwürfen zu legitimieren.” [11/02/2019]

Hambacher Forst (2014): “Ein paar Gedanken zu Solidarität und Gewalt.” [11/02/2019]

Hambacher Forst (2015): “Unsere Scheiße gegen eure Gewalt!” [11/02/2019]

Hambacher Forst (2016): “Zur Gewalt.” [11/02/2019]

Hambacher Forst (2017): “Warum ich Gewaltfreiheit ablehne und die Klimabewegung vielfältige Taktiken braucht – Gedanken einer ‘Zucker im Tank’- Aktivistin.” [11/02/2019]

Hambacher Forst (2018a): “Alle Jahre wieder…” [11/02/2019]

Hambacher Forst (2018b): “Interview mit zwei Aktivistis, aufgenommen kurz nach der Großdemo.” [11/02/2019]

Hambacher Forst Buchprojekt (2015): “Mit Baumhäusern gegen Bagger: Geschichten vom Widerstand im rheinischen Braunkohlerevier.” Osnabrück: Packpapierverlag.

Worldviews and Peace

Gregor, Thomas and Clayton A Robarchek (1996): “Two Paths to Peace: Semai and Mehinaku Nonviolence.” In Thomas Gregor (Ed.): “A Natural History of Peace.”, 159-187. Nashville and London: Vanderbilt University Press.

Pankhurst, Alula A. (2006): “A Peace Ceremony at Arbore.” In Ivo Strecker and Jean Lyndall (Ed.): “The Perils of Peace.”, 247-267. New Brunswick and London: Transaction Publishers.

Pankhurst, Alula A. and Ivo Strecker (2004): “Bury the Spear!” Documentary Educational Resources (DER).

Peace and War in Media

Fraiman, Susan (1995): “Catharine MacKinnon and the Feminist PornDebates.” In American Quarterly 47 (4): 743-749.